What Is The Purpose Of Skin

Nurses need to understand the skin and its functions to identify and manage skin problems. This article, the start in a 2-part series, looks at the skin's structure and key functions. This commodity comes with a self-assessment enabling you to exam your knowledge after reading it

Abstract

Skin diseases impact 20-33% of the population at any 1 fourth dimension, and around 54% of the Great britain population will experience a skin status in a given yr. Nurses notice the peel of their patients daily and information technology is important they sympathise the skin so they tin recognise bug when they ascend. This article, the showtime in a two-office series on the peel, looks at its structure and function.

Citation: Lawton Southward (2019) Skin 1: the construction and functions of the peel. Nursing Times [online]; 115, 12, xxx-33.

Author: Sandra Lawton, Queen'due south Nurse and nurse consultant and clinical lead dermatology, The Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Ringlet downwardly to read the commodity or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download delight try again using a different browser)

- Assess your noesis and gain CPD evidence by taking the Nursing Times Self-cess test

- Read part 2 of this series here

Introduction

Skin diseases affect xx-33% of the Great britain population at any one time (All Parliamentary Grouping on Pare, 1997) and surveys advise around 54% of the UK population will experience a skin status in a given year (Schofield et al, 2009). Nurses will find the skin daily while caring for patients and it is important they sympathise it so they tin can recognise problems when they arise.

The peel and its appendages (nails, pilus and certain glands) class the largest organ in the man trunk, with a surface surface area of 2m2 (Hughes, 2001). The skin comprises 15% of the full adult body weight; its thickness ranges from <0.1mm at its thinnest office (eyelids) to 1.5mm at its thickest office (palms of the hands and soles of the feet) (Kolarsick et al, 2011). This commodity reviews its construction and functions.

Construction of the peel

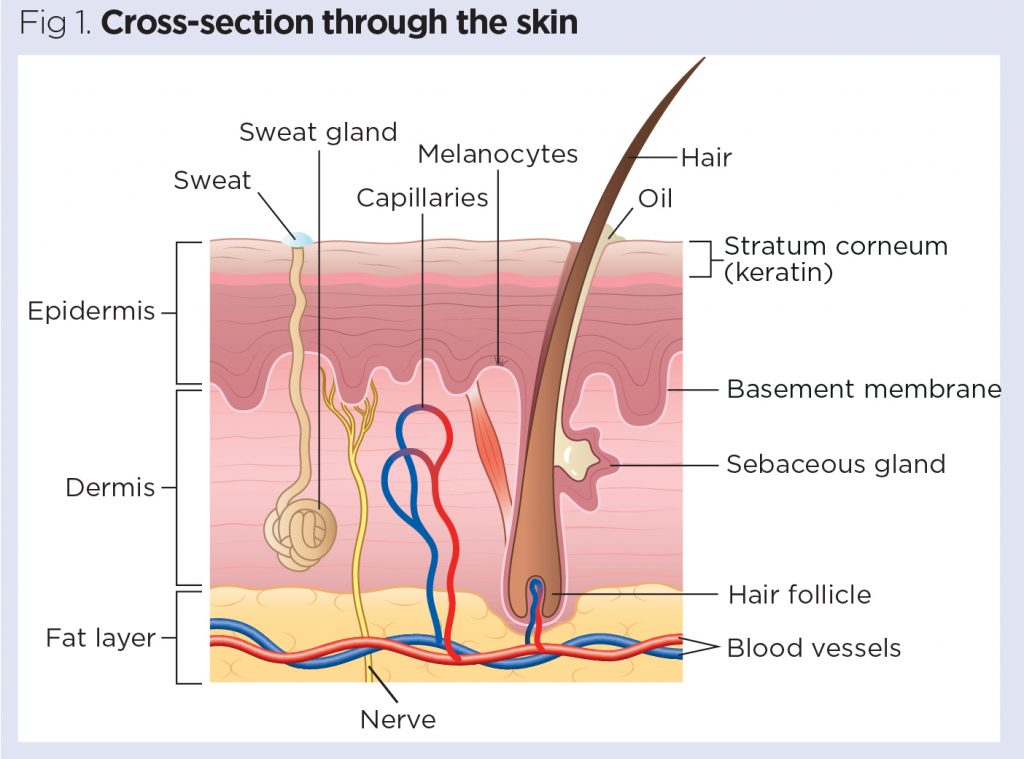

The skin is divided into several layers, as shown in Fig 1. The epidermis is equanimous mainly of keratinocytes. Beneath the epidermis is the basement membrane (besides known as the dermo-epidermal junction); this narrow, multilayered construction anchors the epidermis to the dermis. The layer beneath the dermis, the hypodermis, consists largely of fat. These structures are described below.

Epidermis

The epidermis is the outer layer of the peel, defined as a stratified squamous epithelium, primarily comprising keratinocytes in progressive stages of differentiation (Amirlak and Shahabi, 2017). Keratinocytes produce the protein keratin and are the major building blocks (cells) of the epidermis. As the epidermis is avascular (contains no blood vessels), it is entirely dependent on the underlying dermis for nutrient delivery and waste product disposal through the basement membrane.

The prime role of the epidermis is to deed every bit a concrete and biological barrier to the external environs, preventing penetration by irritants and allergens. At the same time, it prevents the loss of h2o and maintains internal homeostasis (Gawkrodger, 2007; Cork, 1997). The epidermis is composed of layers; virtually body parts take 4 layers, but those with the thickest skin have v. The layers are:

- Stratum corneum (horny layer);

- Stratum lucidum (only found in thick skin – that is, the palms of the hands, the soles of the anxiety and the digits);

- Stratum granulosum (granular layer);

- Stratum spinosum (prickle jail cell layer);

- Stratum basale (germinative layer).

The epidermis also contains other cell structures. Keratinocytes make up effectually 95% of the epidermal jail cell population – the others existence melanocytes, Langerhans cells and Merkel cells (White and Butcher, 2005).

Keratinocytes. Keratinocytes are formed by sectionalisation in the stratum basale. Equally they move up through the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum, they differentiate to form a rigid internal structure of keratin, microfilaments and microtubules (keratinisation). The outer layer of the epidermis, the stratum corneum, is composed of layers of flattened dead cells (corneocytes) that have lost their nucleus. These cells are so shed from the skin (desquamation); this complete process takes approximately 28 days (Fig three).

Between these corneocytes there is a complex mixture of lipids and proteins (Cork, 1997); these intercellular lipids are cleaved down by enzymes from keratinocytes to produce a lipid mixture of ceramides (phospholipids), fat acids and cholesterol. These molecules are arranged in a highly organised fashion, fusing with each other and the corneocytes to form the skin's lipid barrier against water loss and penetration past allergens and irritants (Holden et al, 2002).

The stratum corneum can be visualised every bit a brick wall, with the corneocytes forming the bricks and lamellar lipids forming the mortar. As corneocytes comprise a water-retaining substance – a natural moisturising factor – they attract and hold water. The loftier water content of the corneocytes causes them to swell, keeping the stratum corneum pliable and rubberband, and preventing the germination of fissures and cracks (Holden et al, 2002; Cork, 1997). This is an important consideration when applying topical medications to the skin. These are absorbed through the epidermal barrier into the underlying tissues and structures (percutaneous absorption) and transferred to the systemic circulation.

The stratum corneum regulates the amount and rate of percutaneous absorption (Rudy and Parham-Vetter, 2003). One of the well-nigh important factors affecting this is peel hydration and environmental humidity. In healthy skin with normal hydration, medication tin can only penetrate the stratum corneum by passing through the tight, relatively dry, lipid barrier between cells. When skin hydration is increased or the normal skin bulwark is impaired as a result of peel disease, excoriations, erosions, fissuring or prematurity, percutaneous absorption will be increased (Rudy and Parham-Vetter, 2003).

Melanocytes. Melanocytes are found in the stratum basale and are scattered amidst the keratinocytes along the basement membrane at a ratio of ane melanocyte to x basal cells. They produce the pigment melanin, manufactured from tyrosine, which is an amino acid, packaged into cellular vesicles called melanosomes, and transported and delivered into the cytoplasm of the keratinocytes (Graham-Brown and Bourke, 2006). The main function of melanin is to absorb ultraviolet (UV) radiations to protect u.s.a. from its harmful effects.

Skin colour is determined not by the number of melanocytes, but by the number and size of the melanosomes (Gawkrodger, 2007). It is influenced by several pigments, including melanin, carotene and haemoglobin. Melanin is transferred into the keratinocytes via a melanosome; the colour of the pare therefore depends of the amount of melanin produced by melanocytes in the stratum basale and taken upward by keratinocytes.

Melanin occurs in two primary forms:

- Eumelanin – exists as black and brown;

- Pheomelanin – provides a red colour.

Peel color is as well influenced by exposure to UV radiations, genetic factors and hormonal influences (Biga et al, 2019).

Langerhans cells. These are antigen (micro-organisms and foreign proteins)-presenting cells found in the stratum spinosum. They are role of the trunk's immune system and are constantly on the lookout for antigens in their surroundings so they can trap them and present them to T-helper lymphocytes, thereby activating an immune response (Graham-Brown and Bourke, 2006; White and Butcher, 2005).

Merkel cells. These cells are merely nowadays in very small numbers in the stratum basale. They are closely associated with terminal filaments of cutaneous fretfulness and seem to have a office in sensation, especially in areas of the body such as palms, soles and ballocks (Gawkrodger, 2007; White and Butcher, 2005).

Basement membrane zone

(dermo-epidermal junction)

This is a narrow, undulating, multi-layered structure lying between the epidermis and dermis, which supplies cohesion between the two layers (Amirlak and Shahabi, 2017; Graham-Brownish and Bourke, 2006). It is composed of two layers:

- Lamina lucida;

- Lamina densa.

The lamina lucida is the thinner layer and lies directly beneath the stratum basale. The thicker lamina densa is in straight contact with the underlying dermis. It undulates between the dermis and epidermis and is continued via rete ridges chosen dermal papillas, which contain capillary loops supplying the epidermis with nutrients and oxygen.

This highly irregular junction greatly increases the surface surface area over which the exchange of oxygen, nutrients and waste products occurs betwixt the dermis and the epidermis (Amirlak and Shahabi, 2017).

Dermis

The dermis forms the inner layer of the skin and is much thicker than the epidermis (1-5mm) (White and Butcher, 2005). Situated between the basement membrane zone and the subcutaneous layer, the main role of the dermis is to sustain and support the epidermis. The main functions of the dermis are:

- Protection;

- Cushioning the deeper structures from mechanical injury;

- Providing nourishment to the epidermis;

- Playing an of import office in wound healing.

The network of interlacing connective tissue, which is its major component, is made upward of collagen, in the chief, with some elastin. Scattered within the dermis are several specialised cells (mast cells and fibroblasts) and structures (blood vessels, lymphatics, sweat glands and nerves).

The epidermal appendages also lie within the dermis or subcutaneous layers, but connect with the surface of the skin (Graham-Brown and Bourke, 2006).

Layers of dermis. The dermis is made upward of two layers:

- The more than superficial papillary dermis;

- The deeper reticular dermis.

The papillary dermis is the thinner layer, consisting of loose connective tissue containing capillaries, elastic fibres and some collagen. The reticular dermis consists of a thicker layer of dense connective tissue containing larger blood vessels, closely interlaced elastic fibres and thicker bundles of collagen (White and Butcher, 2005). It also contains fibroblasts, mast cells, nervus endings, lymphatics and epidermal appendages. Surrounding these structures is a gluey gel that:

- Allows nutrients, hormones and waste matter products to pass through the dermis;

- Provides lubrication betwixt the collagen and elastic fibre networks;

- Gives bulk, allowing the dermis to act as a stupor absorber (Hunter et al, 2003).

Specialised dermal cells and structures. The fibroblast is the major cell type of the dermis and its principal function is to synthesise collagen, elastin and the gluey gel within the dermis. Collagen – which gives the skin its toughness and force – makes up lxx% of the dermis and is continually broken downward and replaced; elastin fibres give the skin its elasticity (Gawkrodger, 2007). However both are afflicted past increasing age and exposure to UV radiation, which results in sagging and stretching of the skin as the person gets older and/or is exposed to greater amounts of UV radiation (White and Butcher, 2005).

Mast cells contain granules of vasoactive chemicals (the chief one being histamine). They are involved in moderating allowed and inflammatory responses in the skin (Graham-Dark-brown and Bourke, 2006).

Blood vessels in the dermis form a complex network and play an important part in thermoregulation. These vessels can be divided into two distinct networks:

- Superficial plexus – fabricated upwardly of interconnecting arterioles and venules lying shut to the epidermal edge, and wrapping around the structures of the dermis, the superficial plexus supplies oxygen and nutrients to the cells;

- Deep plexus – found deeper at the border with the subcutaneous layer, its vessels are more substantial than those in the superficial plexus and connect vertically to the superficial plexus (White and Butcher, 2005).

The lymphatic drainage of the skin is important, the main part being to conserve plasma proteins and scavenge foreign cloth, antigenic substances and bacteria (Amirlak and Shahabi, 2017).

About ane meg nervus fibres serve the skin – sensory perception serves a critically important protective and social/sexual function. Complimentary sensory nerve endings are found in the dermis every bit well as the epidermis (Merkel cells) and find hurting, itch and temperature. There are besides specialised receptors – Pacinian corpuscles – that notice pressure and vibration; and Meissner's corpuscles, which are touch on-sensitive.

The autonomic nerves supply the blood vessels and sweat glands and arrector pili muscles (attached to the pilus) (Gawkrodger, 2007).

Hypodermis

The hypodermis is the subcutaneous layer lying beneath the dermis; it consists largely of fat. Information technology provides the main structural back up for the pare, as well every bit insulating the body from common cold and aiding shock absorption. It is interlaced with blood vessels and fretfulness.

Functions of the skin

The skin has 3 main functions:

- Protection;

- Thermoregulation;

- Awareness.

Within this, it performs several important and vital physiological functions, every bit outlined below (Graham-Brown and Bourke, 2006).

Protection

The peel acts as a protective barrier from:

- Mechanical, thermal and other physical injury;

- Harmful agents;

- Excessive loss of moisture and protein;

- Harmful furnishings of UV radiation.

Thermoregulation

Ane of the peel'due south important functions is to protect the body from cold or estrus, and maintain a constant core temperature. This is accomplished by alterations to the claret catamenia through the cutaneous vascular bed. During warm periods, the vessels amplify, the skin reddens and beads of sweat class on the surface (vasodilatation = more blood flow = greater straight heat loss). In cold periods, the blood vessels constrict, preventing oestrus from escaping (vasoconstriction = less blood flow = reduced heat loss). The secretion and evaporation of sweat from the surface of the skin also helps to cool the body.

Sensation

Skin is the 'sense-of-impact' organ that triggers a response if we touch or experience something, including things that may crusade pain. This is important for patients with a skin condition, equally hurting and itching tin can exist farthermost for many and cause smashing distress. As well touch is important for many patients who feel isolated by their pare as a effect of colour, disease or the perceptions of others as many feel the fact that they are seen as dingy or contagious and should not be touched.

Immunological surveillance

The skin is an important immunological organ, made upwardly of fundamental structures and cells. Depending on the immunological response, a variety of cells and chemical messengers (cytokines) are involved. These specialised cells and their functions will be covered later.

Biochemical functions

The peel is involved in several biochemical processes. In the presence of sunlight, a form of vitamin D called cholecalciferol is synthesised from a derivative of the steroid cholesterol in the peel. The liver converts cholecalciferol to calcidiol, which is and so converted to calcitriol (the active chemic form of the vitamin) in the kidneys. Vitamin D is essential for the normal absorption of calcium and phosphorous, which are required for healthy basic (Biga et al, 2019). The skin also contains receptors for other steroid hormones (oestrogens, progestogens and glucocorticoids) and for vitamin A.

Social and sexual office

How an individual is perceived by others is important. People make judgements based on what they run across and may form their first impression of someone based on how that person looks. Throughout history, people accept been judged because of their pare, for instance, due to its colour or the presence of a skin condition or scarring. Pare conditions are visible – in this pare-, dazzler- and image-witting society, the way patients are accepted by other people is an important consideration for nurses.

Summary

This commodity gives an overview of the structure and functions of the skin. Office 2 volition provide an overview of the accompaniment structures of the peel and their functions.

Key points

- The pare is the largest organ in the human body

- Approximately half of the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland population volition experience a pare condition in any given year

- Nurses observe patients' skin daily, so demand to be able to identify problems when they arise

- Fundamental functions of the pare include protection, regulation of body temperature, and sensation

- How others respond to people who accept skin atmospheric condition is an important consideration for nurses

- Examination your knowledge with Nursing Times Self-cess afterward reading this article. If you score fourscore% or more than, you lot will receive a personalised certificate that you can download and store in your NT Portfolio equally CPD or revalidation evidence.

- Accept the Nursing Times Self-cess for this article

References

All Parliamentary Grouping on Skin (1997) An Investigation into the Capability of Service Provision and Treatments for Patients with Skin Diseases in the Uk.

Amirlak B, Shahabi L (2017) Pare Anatomy.

Biga LM et al (2019) Beefcake and Physiology.The integumentary organisation five.1: layers of the peel.

Cork MJ (1997) The importance of skin barrier role. Journal of Dermatological Treatment; 8: Suppl 1, S7-S13.

Gawkrodger DJ (2007) Dermatology: An Illustrated Colour Text. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Graham-Brown R, Bourke J (2006) Mosby's Colour Atlas and Text of Dermatology. London: Mosby.

Holden C et al (2002) Brash best do for the utilise of emollients in eczema and other dry out skin conditions. Journal of Dermatological Treatment; 13: 3, 103-106.

Hughes E (2001) Pare: its structure, role and related pathology. In: Hughes East, Van Onselen J (eds) Dermatology Nursing: A Applied Guide. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Hunter J et al (2003) Clinical Dermatology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific discipline.

Kolarsick PAJ et al (2011) Anatomy and physiology of the skin. Journal of Dermatology Nurses' Association; 3: four, 203-213.

Rudy SJ, Parham-Vetter PC (2003) Percutaneous absorption of topically applied medication. Dermatology Nursing; 15: 2, 145-152.

Schofield J et al (2009) Skin Conditions in the Britain: A Health Intendance Needs Assessment.

White R, Butcher M (2005) The structure and functions of the skin. In: White R (ed) Skin Care in Wound Management: Cess, Prevention and Handling. Aberdeen: Wounds U.k..

Source: https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/dermatology/skin-1-the-structure-and-functions-of-the-skin-25-11-2019/

Posted by: smithuntowent1983.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Purpose Of Skin"

Post a Comment